Statecraft

Institute of Contemporary Art, Newtown (I.C.A.N.)

12 – 28 September 2008

Philipa Veitch, Statecraft, maple, MDF, acrylic, Epson Ultra Chrome print on Chromajet Newsproof, Felt, Thread, 2008

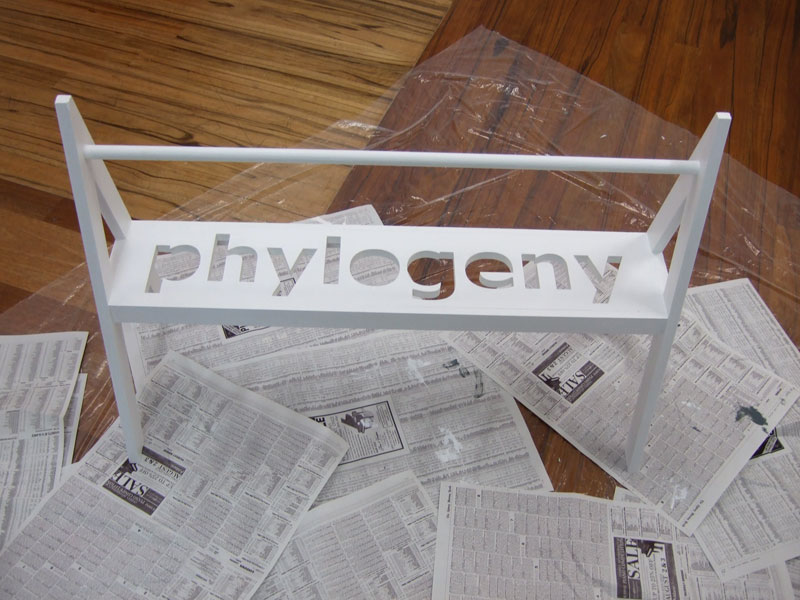

Philipa Veitch, Statecraft / Ontogeny recapitulates Phylogeny, 826mm x 650mm x 360mm, 1090mm x 640mm x 360mm, 900mm x 635mm x 360mm, maple, MDF, acrylic, Epson Ultra Chrome print on Chromajet Newsproof,2008

Philipa Veitch,Vincit qui se vincet, Virile Agitur, Horse blankets, 1670mm x 1560mm,Felt, thread, 2008

Philipa Veitch, Statecraft / Ontogeny recapitulates Phylogeny, 826mm x 650mm x 360mm, 1090mm x 640mm x 360mm, 900mm x 635mm x 360mm, maple, MDF, acrylic, Epson Ultra Chrome print on Chromajet Newsproof, 2008

We are all familiar with the metaphor of the wild horse that must be ‘broken’ in order to be rendered useful to humans. Something precious (that humans also value) is lost, but it is worth the sacrifice in the scheme of things: a greater value is gained, that of constructive human endeavour.

These horse blankets inevitably connote the domestication of a once wild animal: the loss of a free spirit but the gain of a constructive force, albeit by gentle means. For the blankets also symbolise care, even tenderness, put on to alleviate the burden of the saddle, to protect the animal from the elements, or to publicly acknowledge the animal’s achievements in the human realm.

In Statecraft, this narrative of the exchange of wilderness for usefulness is in turn overlaid with references to the transition from less structured to fully institutionalised childhood; the blankets are rendered in the (often nauseating) colour combinations of local primary schools, and embroidered with their mottos. ‘Play the game’, ‘Strive to achieve’, ‘Endeavour’…live up to these mottos and you’ll merit the school equivalent of a trophy blanket.

The paraphernalia of early childhood is also represented by way of pint-sized paint stands. These evoke the encouragement of free expression that pre-dates more goal-orientated school proper: unlike what happens once formal education begins, the innumerable daubs of the pre-schooler are all about process and experimentation, never judged on aesthetic merit. Further reference to the instrumentalisation of creativity is found in the newspapers that ‘catch the drips’ from the paint stands: reproductions of actual print advertisements that co-opt the aura of the artist to promote consumer goods.

Philipa Veitch has conceived this work from multiple points of personal investment: as an artist, as a parent, and an educator in training. Points of intersection of these varied roles are many, but a central one is the relationship — or trade off — between creativity and productivity in human existence, and in particular in contemporary capitalist societies such as ours. As the artist asks, does creativity provide at least the opportunity for an autonomous space to ‘be’, to think, or is this space already given over to the overwhelming human drive to ‘produce’ (or ‘strive’ or ‘endeavour’), to engage in a (quantifiable and justifiable) project?

Carved into the paint stands is the intriguing text, ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’. This is the name of a once influential scientific theory that proposed that in its process of development (ontogeny), the human embryo goes through stages similar to the evolution of more ‘advanced’ species from less complex ones (phylogeny). Hence the idea — which is still pervasive today despite the discrediting of this 19th century theory — that at one point the human embryo resembles that of a fish, then a reptile, then an ape. If the microcosm cannot but reproduce the macrocosm, the dominant discourse becomes biological determinism, which leaves little room for any deviations by way of ‘culture’ or human agency. (For many structuralists who become parents the argument that ‘it’s all culture’ becomes less and less convincing. Here I am reminded also of recent arguments made in the context of ethical debates surrounding emerging technologies of genetic enhancement: why should we deny ourselves biological advantage when we not only condone, but actively seek and revere, social advantage?)

Statecraft weaves together several themes: the artist’s diurnal quest to provide her children with both the means to survive but also the means to actively question and imagine a different world; her ongoing analysis of her own artistic practice and the agency of art in the social realm; her alarm at the intensifying cooptation of creativity and play into economic discourse and corporate and government policy-speak; and her awareness of an insidious ‘culture of servitude’ that is purveyed even by those forces that symbolize autonomous thought such as education and art. By activating the links between Veitch’s concerns at a personal and political level,Statecraft ends by implicating us in and alerting us to pressing questions of social responsibility.

Jacqueline Millner, September 2008