Nature Strip

Exhibited in Blaugrau / October 19 – 22 2000

and The Degree Show, Sydney College of the Arts / November 21 – December 8 2000

Photographs, drawings and reflections on a 1999 Asialink Visual Arts residency in Beijing

“The fundamental choice of an artist lies in the apprehension of a certain beauty – a hidden secret lying dormant. There is no doubt that I came to literature seduced and fascinated by this certain type of beauty which influenced all my mental speculations, even the most abstract. So the time would have to come when I could make my way along the paths of art to that sacred space where my charms and spells were celebrated.” Witold Gombrowicz, Pornnographia

“I never fail, when approaching Peking, to experience a heightened sense of being at the very edge of a new adventure.” Felix Green, Peking

I arrived in Beijing in the midst of manic preparations for the Fiftieth Anniversary, a massive celebration commemorating fifty years to the day since Mao Zedong and the remaining troops of the Red Army marched into Tiananmen Square on October 1, 1949. Beijing at this point in time resembled a giant construction site, with buildings and streets being alternately demolished and then made anew in anticipation of this unprecedented event. Every street corner, shop and public building seemed to be the focus of an intensive process of redecoration, adorned with newly constructed traditional pagodas and other architectural motifs, complicated potted flower displays, dioramas, fake Chinese landscapes, flags, signs and banners. On television, classic Chinese films were screened every night, while every channel seemed to be broadcasting it’s own version of Mao’s life story in the form of lengthy telemovies and mini series’.

Sprouting amidst this profligation of revolutionary nostalgia, were hundreds of examples of new capitalist enterprises. The traditional shopping street Wangfujing had been transformed into a mall, Starbucks coffee shops were popping up amongst the now old hat Macdonald’s, KFC’s and Pizza Huts, while China’s biggest shopping centre, The Great Mall, was in the process of being erected right next to my apartment on Chaoyang Lu. These cliched images of the “new” China soon became absorbed within and even subsumed by the profusion of sensations and images I was to experience during my four month residency in The Peoples Republic.

The Anniversary – celebrated on a mammoth scale with marches, formations and dances by literally thousands of military personnel, school children, work units and an array of different groups representing every county and nationality from around the country – came and passed. Commerce and movement on the micro scale seemed to exist in every nook and cranny, while the overabundance of “manpower” meant manual labour became the preferred means of completing tasks that would normally be mechanised in wealthier, less populated countries. Thus, large scale construction and demolition projects appeared in many cases to be accomplished by mass-scale physical labour, while cyclists pedalling purpose built vehicles transported everything from teetering loads of produce to fridges and other large and heavy household goods. The accumulated historical traumas of the last two or three hundred years were seemingly transmogrified into a collective desire to erase past mistakes through a process of complete urban renewal.

In the old section of the city of Guangzhou in the more tropical south, almost every section of its crowded narrow streets was devoted to selling a particular type of food or other product. In the section devoted to traditional Chinese medicines one could find fungi, dried seahorses, beetles and scorpions. Other areas specialised in live food such as chickens, ducks, snakes and dogs, while other streets sold only seafood. Moving through the streets, I passed through sections that sold only Hello Kitty, dried sharks fin, hairclips, or motorcycle parts.

In the rural areas, most if not all the available arable land was used for food production, which was farmed by hand in small, human scale plots. In some places, entire mountains had literally been terraced to allow rice and other crops to be propagated. The persistence, skill, ingenuity and effort required to grow food and feed such a large population at times seemed overwhelming. At the same time, and with the combined effects of a consumer driven economic boom and an influx of foreign investment, many areas in rural China were experiencing a period of rapid economic, residential, and industrial development, with many rural areas being transformed through the growth of small towns and secondary industries. With many large cities still retaining tangible links to rural life, and rural areas now being transformed by urban developments, the effect overall was one of turbulence and dislocation, a hybrid landscape neither urban nor rural, but a rapidly evolving combination of the two.

As an outsider hindered by a limited grasp of the language, my experience of China was mediated through images, sounds, tastes and smells. While this can no doubt be said of any nation or culture, my perception of China was one of overwhelming physicality, of an existence grounded in the realities of land, shelter, food, trade, movement, communication and camaraderie. As I developed greater confidence in speaking and understanding a truncated form of Mandarin, day to day interactions took on a greater significance, adding up to form a disconnected but increasingly meaningful assortment of observations and experiences. There were many times when I experienced a sense of going back to square one. Bereft of my habitual mechanisms of participating in typical day to day situations, I was coaxed into resourcefulness and a renewed ability to absorb and respond to the many novel circumstances I was to find myself in.

Lost in the morass of this alien culture, I increasingly found my awareness being absorbed in the minutiae of the many forms and environments I experienced as I travelled around the country. These ecologies were alternately sublime and scatological, apocalyptic, kitsch, and beautiful. Abstracted by virtue of their novelty, they became detached from their usual functions, existing as pure forms within an alienating landscape.

The drawings and photographs I developed in response to the residency reflected my changing apprehension of these forms, shifting between perceptions that alternately grounded them within their cultural and environmental specificity, then allowed them to become detached from that groundedness, shrouded within a field of abstraction and association.

Since I commenced the residency in August 1999, I have produced and exhibited two major bodies of work in response to the experience. Duckmilk, a suite of 50 faxed, black and white drawings on A4 paper I produced for the group exhibition Toxic, explored the side effects of the new China – an outsiders view of Chinese trash culture purloined from junk mail catalogues, teenage fashion magazines and comic books, as well as images of urban backlots, streetscapes, and fading anniversary paraphernalia. Combining to form an accretion of disparate affects, and developed in response to the emerging youth cultures and urban reconstructions of Beijing and Guangzhou, the piece attempted to elaborate on the relationship between China’s younger generations and the ecology of China’s new ruins – environmental waste, development and urban and social decay.

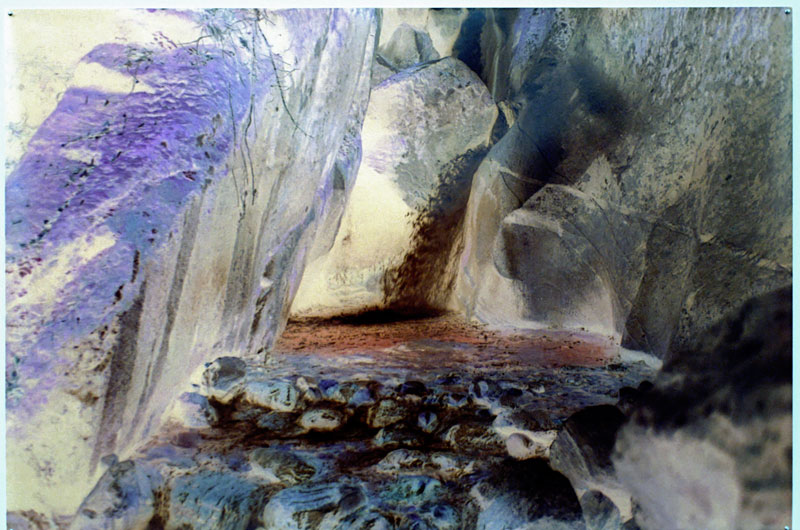

The four large scale photographs in Nature Strip, to be exhibited as part of the final year exhibition in November 2000, were of more ambiguous forms, in the main derived from my experiences of travelling in some of the more remote areas of rural China. Printed as mural sized L.E.D. prints, and resembling a colour negative, the images of a waterfall, traditional landscape, and the ambiguous debris of urban reclamation reflected on notions of regeneration and timelessness. The unusual tonal arrangements of the prints lent an air of unreality to the schema, of a delay or refraction between perception and the object of the gaze. Bringing together the oppositions of natural and man-made forms, the images are suggestive of a slippage between the two modes.

This is an extract from my 2001 Masters thesis “Nature Strip”.