The Wit of the Staircase

2SER FM / 1992

Sleepwalker / Caravan – Experimental Art Foundation / curated by Bronia Iwanczak / 1998

Oblique – the Otira project / curated by Julaine Stephenson / 1999

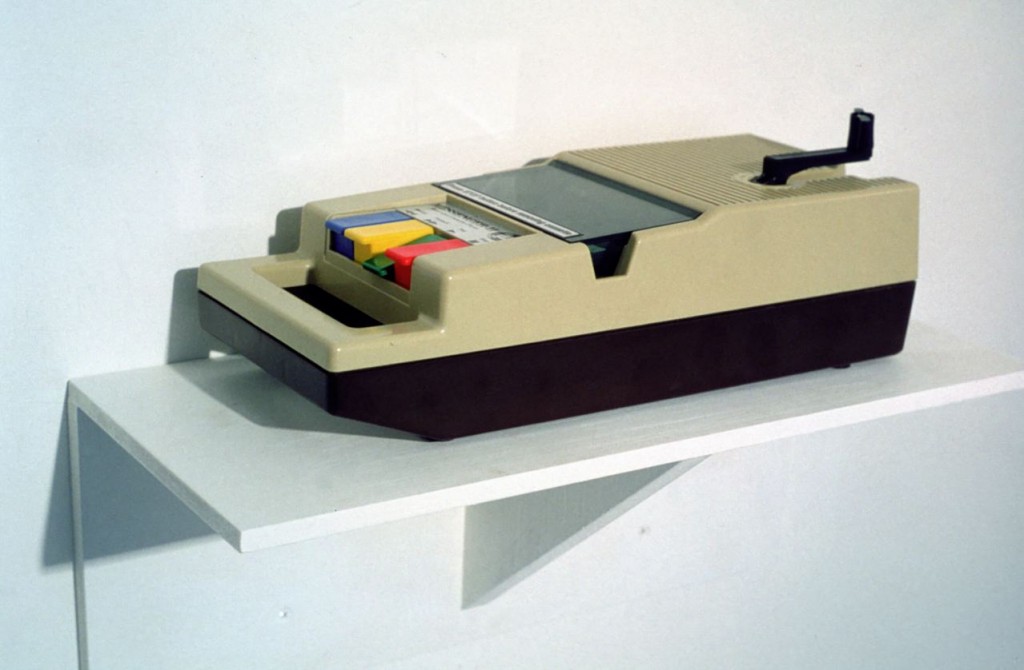

Philipa Veitch, The Wit of the Staircase, audio recordings of people describing their daydreams, played on a handwinding cassette player, exhibited in Sleepwalker, curated by Bronia Iwanczak, 1998

The Wit of the Staircase is the title of a work I produced between 1992 and 1999. Developing out of a longstanding interest in the process or phenomena of daydreaming, I spent seven years accumulating a series of tape recorded interviews with a range of people about their daydreams and recurring thoughts, memories and fantasies. The initial recordings were broadcast on radio 2SERFM in 1992. The project then went into hibernation, and was later expanded into a 60 minute audio work which was exhibited as part of the exhibition Sleepwalker (curated by Bronia Iwanczak) at the Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide in 1998, where it was shown / played on a handwinding (ie battery-less / power – less) cassette player, purchased through the mail from an evangelical Christian missionary organisation. It was expanded again to 120 minutes, and played on two of these devices, for the exhibition Oblique (curated by Julaine Stephenson), in Otira, New Zealand, in 1999.

“I think what people do in love and things like that is all largely a bit of a daydream. I mean I think that you sort of write the script about love a lot of the time, or initiate it, or embark on something like that from a daydream.”

“I have these daydreams about devouring my lovers. Sometimes I’m eating them, not necessarily eating them so much as taking in the full substance of them which can’t be done through sexual intercourse or anything like that. I mean it’s the will to devour the lover, to completely subsume them, so that you can take them inside and they can never escape, ever again. And you, you have the wholeness of them, all wrapped up inside you.”

“Most of my daydreams are pretty contentless, total denial of self. Or if not totally contentless just sort of a, delving into nothingness, like a total dilution of everything that’s around me, as though it’s as if everything is really pastelised, so I might be on a bus, or sitting amongst a group of people, and everybody just sort of fades off, and everything gets very light coloured, there’s a real lack of contrast and everything seems very distant. I also, I’ve noticed when I start to daydream quite a bit I hallucinate spatially a real lot, what I mean by that is something that’s two metres away, might look twenty metres away and vice versa. That’s a lot I have that.”

“I get kind of uncontrollable daydreams as well, like sometimes when I’m going to sleep, I get this thing where I’m really tiny and everything’s huge, and it’s all got incredible surfaces to it, and it’s like, I’m overwhelmed by the feel of the texture of everything.”

I started making The Wit of the Staircase when I was about 21. I spent about a year working at a public radio station doing sound based work, mostly interviews but also more abstract compositions and observational pieces. At a certain point towards the end of 1992 I began to move completely away from collecting observations and opinions about various physical or social phenomena, and attempted to retrieve some information about the structures and forms of private thoughts. I decided that the word daydreaming, as imprecise and fanciful as it might have sounded, was probably the most appropriate term to use in this context, as it referred to the free form, uninhibited flow of memories, fantasies and thoughts I wanted to investigate.

I initially did a series of five or six interviews, broadcasting the edited versions in a straightforward, documentary-like format. The following year, and for several years after that, I continued to return to the subject of daydreaming, this time with the intention of compiling a kind of loosely structured phenomenology of daydreaming. This phenomenology would seek to determine to what extent were daydreams sensed in terms of touch, sight, smell etc; were most daydreams memories or fantasies, regrets, or thoughts of ideal situations or futures? Did people have certain daydreaming habits, or recurring daydreams, and were these deliberate or something that came to their minds unbidden? I asked each person to recount their daydreams as a form of unstructured narrative, sensing that this would be the best way to get a true sense of the feelings and thoughts that crossed through their minds as they went about their day to day lives.

I based my questions initially on observations of my own daydreams, and what I imagined others might consist of. I discovered that the process of conducting the interviews extended the awareness of the possibilities of daydreaming in both myself and the subject I was interviewing, allowing me to expand the scope of my enquiries with each new interview. A definite process of transference seemed to occur, as I drew attention to forms of daydreaming people had not previously considered, while my awareness of the trajectories and forms of my own thoughts became more acute.

I found that most of my interviewees, and indeed I myself, had never really made a conscious effort to systematically observe the contents of waking thoughts. Many people I spoke to were wary of exposing what they rightfully considered to be a vulnerable and very private aspect of their existence, while others seemed to experience genuine difficulty in actually recalling any specific details of their daydreams. The difficulty in recalling or reconstructing a daydream seemed to arise from their emeshedness with lived reality or the state of wakefulness. A daydream could emerge seamlessly from an observation gleaned from ones immediate environment, while at the same time erasing our consciousness of existing in that moment.

“Put it this way, sometimes there are definite times when I’ve believed they’ve happened, that they’ve actually happened and I’ve mixed it up with reality whatever that’s meant to mean, but I’ve actually started talking to people as if this thing has happened. Like or, whatever, it may have been something slight, and I’m arguing with them till I’m blue because I’m always right, but that they’ve got it wrong and they’ve forgotten, when it’s actually been a dream, or a daydream.”

Daydreams can act as a kind of psychic glitch within the continuity of conscious perception, a lapse in our attention which disorders our habitual apprehension of being. Daydreams infest time, colonising existence with chimeras and obliterating presence. At the same time, they endow us with the ability to telescope unstable identities, forming a mechanism with which we are able to rapidly project ourselves into an infinite array of hypothetical situations, in effect dissolving time. Daydreams therefore can be considered as a hinge or switch that allow us to modify our level of engagement with the world and with an array of inner states.

“I fantasise a lot about my death. Drowning, being murdered, um, I fantasise about someone in my family’s death too, like my father, if he died, if I want to make myself feel sad….”

“So you daydream all the time? What sort of things do you think about?”

“ I guess it depends what’s been going on, and if I’ve been watching lots of cartoons, they’re going to affect my daydreams. TV, and sort of sex as well, sometimes, just about everyone I’m sure. But the cartoons that’s interesting because it sort of adds a bit of unreality to it, so I’ll imagine things that couldn’t possibly happen, happening, like cars crashing into walls, and things blowing up, maybe bushes catching fire, or, you see something happen and you imagine a sequence of events that would follow, in the cartoon world, that in the real world doesn’t.”

The Wit of the Staircase “samples” these glitches and chimerical images. Jettisoned from a mobile and organic existence, and contained now within the mechanism of a portable, hand-operated tape player, the daydreams cease to evolve and are instead preserved as a remnant, degraded to a new and static existence within the realm of objects, the domestic, the everyday. What will these remnants mean when played again minutes, weeks, or years after they have been recorded, erased now from the living memory of the speaker?

The habit of forgetting, of dissolving our attention in daydreams, allows us to experience existence as a delay, as a momentary crisis of being. As we turn the handle, our hand re-forms word by word the sounds of lost thoughts, a moment which for the daydreamer was turned inward, directed away from the images, sounds and feelings of the world, a moment when they let their attention fall away from the world and from themselves. These forlorn thoughts themselves become objects of play, an off chance to listen in on someone else’s thoughts and to reflect on our own. By playing-with or re-playing the daydreams, we re-activate a circuit between the speaker, tape machine and ourselves, the listener, re-assigning the qualities of everyday objects and spaces, allowing them to become porous, more resistant to their pre-determined destinies. Voice and object become intertwined, and the moment of daydreaming, of falling away, is captured, then passed over again, becoming ever more distant with each repetition.

Philipa Veitch

This is edited extract from my 2001 Masters thesis, Nature Strip